Introduction:

Natural Language Processing (NLP) is a vast area of Computer Science that is concerned with the interaction between Computers and Human Language[1].

Within NLP many tasks are – or can be reformulated as – classification tasks. In classification tasks we are trying to produce a classification function which can give the correlation between a certain ‘feature’ and a class

. This Classifier first has to be trained with a training dataset, and then it can be used to actually classify documents. Training means that we have to determine its model parameters. If the set of training examples is chosen correctly, the Classifier should predict the class probabilities of the actual documents with a similar accuracy (as the training examples).

After construction, such a Classifier could for example tell us that document containing the words “Bose-Einstein condensate” should be categorized as a Physics article, while documents containing the words “Arbitrage” and “Hedging” should be categorized as a Finance article.

Another Classifier could tell us that mails starting with “Dear Customer/Guest/Sir” (instead of your name) and containing words like “Great opportunity” or “one-time offer” can be classified as spam.

Here we can already see two uses of classification models: topic classification and spam filtering. For these purposes a Classifiers work quiet well and perform better than most trained professionals.

A third usage of Classifiers is Sentiment Analysis. Here the purpose is to determine the subjective value of a text-document, i.e. how positive or negative is the content of a text document. Unfortunately, for this purpose these Classifiers fail to achieve the same accuracy. This is due to the subtleties of human language; sarcasm, irony, context interpretation, use of slang, cultural differences and the different ways in which opinion can be expressed (subjective vs comparative, explicit vs implicit).

In this blog I will discuss the theory behind three popular Classifiers (Naive Bayes, Maximum Entropy and Support Vector Machines) in the context of Sentiment Analysis[2]. In the next blog I will apply this gained knowledge to automatically deduce the sentiment of collected Amazon.com book reviews.

The contents of this blog-post is as follows:

- Basic concepts of text classification:

- Tokenization

- Word normalization

- bag-of-words model

- Classifier evaluation

- Naieve Bayesian Classifier

- Maximum Entropy Classifier

- Support Vector Machines

- What to Expect

1. Basic Concepts

Tokenization:

Tokenization is the name given to the process of chopping up sentences into smaller pieces (words or tokens). The segmentation into tokens can be done with decision trees, which contains information to correctly solve the issues you might encounter. Some of these issues you would have to consider are:

- The choice for the delimiter will for most cases be a whitespace (“We’re going to Barcelona” -> [“We’re”, “going”, “to”, “Barcelona.”]), but what should you do when you come across words with a white space in them (“We’re going to The Hague.”->[“We’re”, “going”,”to”,”The”, “Hague”]).

- What should you do with punctuation marks? Although many tokenizers are geared towards throwing punctuation away, for Sentiment analysis a lot of valuable information could be deduced from them. ! puts extra emphasis on the negative/positive sentiment of the sentence, while ? can mean uncertainty (no sentiment).

- “, ‘ , [], () can mean that the words belong together and should be treated as a separate sentence. Same goes for words which are bold, italic, underlined, or inside a link. If you also want to take these last elements into considerating, you should scrape the html code and not just the text.

Word Normalization:

Word Normalization is the reduction of each word to its base/stem form (by chopping of the affixes). While doing this, we should consider the following issues:

- Capital letters should be normalized to lowercase, unless it occurs in the middle of a sentence; this could indicate the name of a writer, place, brand etc.

- What should be done with the apostrophe (‘); “George’s phone” should obviously be tokenized as “George” and “phone”, but I’m, we’re, they’re should be translated as I am, we are and they are. To make it even more difficult; it can also be used as a quotation mark.

- Ambigious words like High-tech, The Hague, P.h.D., USA, U.S.A., US and us.

Bag-of-words:

After the text has been segmented into sentences, each sentence has been segmented into words, the words have been tokenized and normalized, we can make a simple bag-of-words model of the text. In this bag-of-words representation you only take individual words into account and give each word a specific subjectivity score. This subjectivity score can be looked up in a sentiment lexicon[7]. If the total score is negative the text will be classified as negative and if its positive the text will be classified as positive.

Classifier Evaluation:

For determining the accuracy of a single Classifier, or comparing the results of different Classifier, the F-score is usually used. This F-score is given by

where is the precision and

is the recall. The precision is the number of correctly classified examples divided by the total number of classified examples. The recall is the number of correctly classified examples divided by the actual number of examples in the training set.

2. Naive Bayes:

Naive Bayes [3] classifiers are studying the classification task from a Statistical point of view. The starting point is that the probability of a class is given by the posterior probability

given a training document

. Here

refers to all of the text in the entire training set. It is given by

, where

is the

attribute (word) of document

.

Using Bayes’ rule, this posterior probability can be rewritten as:

Since the marginal probability is equal for all classes, it can be disregarded and the equation becomes:

The document belongs to the class

which maximizes this probability, so:

Assuming conditional independence of the words , this equation simplifies to:

Here is the conditional probability that word i belongs to class

. For the purpose of text classification, this probability can simply be calculated by calculating the frequency of word

in class

relative to the total number of words in class

.

We have seen that we need to multiply the class probability with all of the prior-probabilities of the individual words belonging to that class. The question then is, how do we know what the prior-probabilities of the words are? Here we need to remember that this is a supervised machine learning algorithm: we can estimate the prior-probabilities with a training set with documents that are already labeled with their classes. With this training set we can train the model and obtain values for the prior probabilities. This trained model can then be used for classifying unlabeled documents.

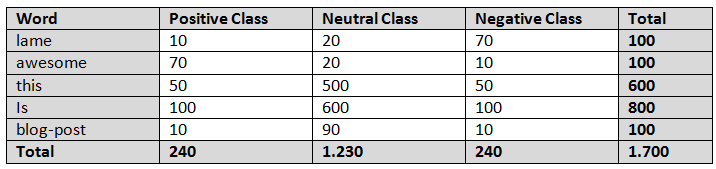

This is relatively easy to understand with an example. Lets say we have counted the number of words in a set of labeled training documents. In this set each text document has been labeled as either Positive, Neutral or as Negative. The result will then look like :

From this table we can already deduce each of the class probabilites:

,

,

.

If we look at the sentence “This blog-post is awesome.”, then the probabilities for this sentence belonging to a specific class are:

This sentence can thus be classified in the positive category.

3. Maximum Entropy:

The principle behind Maximum Entropy [4] is that the correct distribution is the one that maximizes the Entropy / uncertainty and still meets the constraints which are set by the ‘evidence’.

Let me explain this a bit more. In Information Theory, the word Entropy is used as a unit of measure for the unpredictability of the content of information. If you would throw a fair dice, each of the six outcomes have the same probability of occuring (1/6). Therefore you have maximum uncertainty; an entropy of 1. If the dice is weighted you already know one of the six outcomes has a higher probability of occuring and the uncertainty becomes less. If the dice is weighted so much that the outcome is always six, there is zero uncertainty in the outcome and hence the information entropy is also zero.

The same applies to letters in a word (or words in a sentence): if you assume that every letter has the same probability of occuring you have maximum uncertainty in predicting the next letter. But if you know that letters like E, A, O or I have a higher probability of occuring you have less uncertainty.

Knowing this, we can say that complex data has a high entropy, patterns and trends have lower entropy, information you know for a fact to be true has zero entropy (and therefore can be excluded).

The idea behind Maximum Entropy is that you want a model which is as unbiased as possible; events which are not excluded by known constraints should be assigned as much uncertainty as possible, meaning the probability distribution should be as uniform as possible. You are looking for the maximum value of the Entropy. If this is not entirely clear, I recommend you to read through this example.

The mathematical formula for Entropy is given by , so the most likely probability distribution

is the one that maximizes this entropy:

It can be shown that the probability distribution has an exponential form and hence is given by:

,

where is a feature function,

is the weight parameter of the feature function and

is a normalization factor given by

.

This feature function is an indicator function, which is expresses the expected value of the chosen statistics (words) in the training set. These feature functions can then be taken as constraints for the classification of the actual dataset (by eliminating the probability distributions which do not fit with these constraints).

Usually, the weight parameters are automatically determined by the Improved Iterative Scaling algorithm. This is simply a gradient descent function which can be iterated over until it converges to the global maximum. The pseudocode for the this algorithm is as follows:

- Initialize all weight parameters

to zero.

- Repeat until convergence:

- calculate the probability distribution

with the weight parameters filled in.

- for each parameter

calculate

. This is the solution to:

- update the value for the weight parameter:

- calculate the probability distribution

In step 2b is given by the sum of all features in the training dataset d:

Maximum Entropy is a general statistical classification algorithm and can be used to estimate any probability distribution. For the specific case of text classification, we can limit its form a bit more by using word counts as features:

(1)

4. Support Vector Machines:

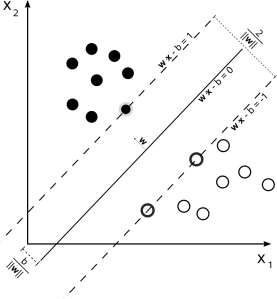

Although it is not immediatly obvious from the name, the SVM algorithm is a ‘simple’ linear classification/regression algorithm[6]. It tries to find a hyperplane which seperates the data in two classes as optimally as possible.

Here as optimally as possible means that as much points as possible of label A should be seperated to one side of the hyperplane and as points of label B to the other side, while maximizing the distance of each point to this hyperplane.

In the image above we can see this illustrated for the example of points plotted in 2D-space. The set of points are labeled with two categories (illustrated here with black and white points) and SVM chooses the hypeplane that maximizes the margin between the two classes. This hyperplane is given by

where is a n-dimensional input vector,

is its output value,

is the weight vector (the normal vector) defining the hyperplane and the

terms are the Lagrangian multipliers.

Once the hyperplane is constructed (the vector is defined) with a training set, the class of any other input vector

can be determined:

if then it belongs to the positive class (the class we are interested in), otherwise it belongs to the negative class (all of the other classes).

We can already see this leads to two interesting questions:

1. SVM only seems to work when the two classes are linearly separable. How can we deal with non-linear datasets? Here I feel the urge to point out that the Naive Bayes and Maximum Entropy are linear classifiers as well and most text documents will be linear. Our training example of Amazon book reviews will be linear as well. But an explanation of the SVM system will not be complete without an explanation of Kernel functions.

2. SVM only seems to be able to separate the dataset into two classes? How can we deal with datasets with more than two classes. For Sentiment Classification we have for example three classes (positive, neutral, negative) and for Topic Classification we can have even more than that.

Kernel Functions:

The classical SVM system requires that the dataset is linearly separable, i.e. there is a single hyperplane which can separate the two classes. For non-linear datasets a Kernel function is used to map the data to a higher dimensional space in which it is linearly separable. This video gives a good illustation of such a mapping. In this higher dimensional feature space, the classical SVM system can then be used to construct a hyperplane.

Multiclass classification:

The classical SVM system is a binary classifier, meaning that it can only separate the dataset into two classes. To deal with datasets with more than two classes usually the dataset is reduced to a binary class dataset with which the SVM can work. There are two approaches for decomposing a multiclass classification problem to a binary classification problem: the one-vs-all and one-vs-one approach.

In the one-vs-all approach one SVM Classifier is build per class. This Classifier takes that one class as the positive class and the rest of the classes as the negative class. A datapoint is then only classified within a specific class if it is accepted by that Class’ Classifier and rejected by all other classifiers. Although this can lead to accurate results (if the dataset is clustered), a lot of datapoints can also be left unclassified (if the dataset is not clustered).

In the one-vs-one approach, you build one SVM Classifier per chosen pair of classes. Since there are possible pair combinations for a set of N classes, this means you have to construct more Classifiers. Datapoints are then categorized in the class for which they have received the most points.

In our example, there are only three classes (positive, neutral, negative) so there is no real difference between these two approaches. In both approaches we have to construct two hyperplanes; positive vs the rest and negative vs the rest.

What to expect:

For the purpose of testing these Classification methods, I have collected >300.000 book reviews of 10 different books from Amazon.com. I will use a part of these book reviews for training purposes and a part as the test dataset. In the next few blogs I will try to automatically classify the sentiment of these reviews with the four models described above.

—————————————-

[1] Machine Learning Literature:

Foundations of Statistical Natural Language Processing by Manning and Schutze,

Machine Learning: A probabilistic perspective by Kevin P. Murphy,

Foundations of Machine Learning by Mehryar Mohri

[2]Sentiment Analysis literature:

There is already a lot of information available and a lot of research done on Sentiment Analysis. To get a basic understanding and some background information, you can read Pang et.al.’s 2002 article. In this article, the different Classifiers are explained and compared for sentiment analysis of Movie reviews (IMDB). This research was very close to Turney’s 2002 research on Sentiment Analysis of movie reviews (see article). You can also read Bo Pang and Lillian Lee’s 2009 article , which is more general in nature (about the challenges of SA, the different ML techniques etc.)

There are also two relevant books: Web Data Mining and Sentiment Analysis, both by Bing Liu. And last but not least, works of Socher are also quiet interesting (see paper, website containing live demo); it even has inspired this kaggle competition.

[3] Naive Bayes Literature:

Machine Learning by Tom Mitchel, Stanford’s IR-book, Sebastian Raschka’s blog-post, Stanford’s online NLP course.

[4]Maximum Entropy Literature:

Using Maximum Entropy for text classification (1999), A simple introduction to Maximum Entropy models (1997), A brief MaxEnt tutorial, another good MIT article.

[6]SVM Literature:

This youtube video gives a general idea about SVM. For a more technical explanation, this and this article can be read. Here you can find a good explanation as well as a list of the mostly used Kernel functions. one-vs-one and one-vs-all.

[7] Sentiment Lexicons:

I have selected a list of sentiment analysis lexicons; most of these were mentioned in the Natural Language Processing course, the rest are from stackoverflow.

- WordStat sentiment Dictionary; This is probably one of the largest lexicons freely available. It contains ~14.000 words ( 9164 negative and 4847 positive words ) and gives words a binary classification (positive or a negative ) score.

- Bill McDonalds 2014 Master dictionary, containing ~85.000 word

- Harvard Inquirer; Contains about ~11.780 words and has a more complex way of ‘scoring’ words; each word can be scored in 15+ categories; words can be Positiv-Negative, Strong-Weak, Active-Passive, Pleasure-Pain, words can indicate pleasure, pain, virtue and vice etc etc

- SentiWordNet; gives the words a positive or negative score between 0 and 1. It contains about 117.660 words, however only ~29.000 of these words have been scored (either positive or negative).

- MPQA; contains about ~8.200 words and binary classifies each word (as either positive or as negative). It also gives additional information such as whether a word is an adjective or a noun and whether a word is ‘strong subjective’ or ‘weak subjective’.

- Bing Liu’s opinion lexicon; contains 4.782 negative and 2.005 positive words.

Including Emoticons in your dictionary;

None of the dictionaries described above contain emoticons, which might be an essential part of text if you are analyzing social media. So how can we include emoticons in our subjectivity analysis? Everybody knows is a positive and

is a negative emoticon but what exactly does

mean and how is it different from :-/?

There are a few emoticon sentiment dictionaries on the web which you could use; Emoticon Sentiment Lexicon created by Hogenboom et. al., containing a list of 477 emoticons which are scored either 1 (positive), 0 (neutral) or -1 (negative). You could also make your own emoticon sentiment dictionary by giving the emoticons the same score as their meaning in words.

11 gedachten over “Text Classification and Sentiment Analysis”

Nice article Ahmeet. Also, would love to hear your thoughts on techniques outside of bag-of-words model. I had used random forest bag-of-words with tf-idf tokenizer for prediction, gave decent results though wl try these too….

Thanks for the advice Prdeepak! I will indeed also look into Text Classifier methods like the Naive Bayes, Maximum Entropy and SVM. The biggest reason to start with bag-of-words is that it is handy to determine the most effective features which can be used with these classifiers.

Very nice and well-explained article with list of must-read papers on sentiment analysis. Thank you so much, Ahmet!